5 Centimeters per Second

…they say it’s five centimeters per second. The speed of a falling cherry petal. Five centimeters per second.

According to the hit 2007 animated short film, 5 Centimeters per Second 1, this is the speed at which cherry petals fall.

Of course, I’m skeptical, and as a physicist I want to model the heck out of this.

So, in this article I would like to propose a model for a thin, circular flower petal to be the spherical cow of flower petals.

The Model

Let’s define our system.

We have a circular, flat flower petal with radius $R$ that does not bend.

The flower petal has a mass surface density of $\sigma$ and a corresponding mass of $M = \sigma \pi R^2$ and area of $A = \pi R^2$.

The flower petal’s center of mass (CM) is labeled with two Cartesian coordinates ($x$ and $y$) (the horizontal and upward directions).

Due to the circular symmetry, we will not consider a 3rd dimension of movement.

The angle made between the disk petal and the horizontal is $\theta$.

In total this gives us three degrees of freedom.

We can measure the radial direction along the disk petal with the radius coordinate $h$.

We will be dealing with dispersive forces in a non-relativistic setting, so Newtonian theory will be suitable here.

Forces

Using Newton’s 2nd law of motion we have

$$ M \ddot r_{CM} = \sum_i F_i $$

for the CM equation of motion.

Since our object is extended we have

$$ I \ddot \theta = \sum_i \tau_i $$

for rotations along the $\theta$ angular direction about the CM.

For our setup we have two main sources of force: gravity and air resistance.

Starting with the easiest, the gravity force.

The force of gravity can be written as

$$ F_g = - M g \hat y $$

Nicely for us, the force of gravity generates no torque about the CM so $\tau_g = 0$.

Now for the hard part: the air force.

Air Force

We can sketch the air force as $F_{air} = -k v$.

We can interpret it as a resistive force that acts against moving objects.

The $k$ is the proportionality parameter that depends on the properties of our petal—like its mass, composition, state, and geometry—while $v$ is the relative velocity of the object to the air.

Constant $k$ Air Force

To get a feel for this force let’s consider the simplest case where $k$ is a constant scalar.

To make our first foray as simple as possible we will assume that the flower petal has no rotation.

Furthermore, we only assume downward motion, so we will only have to consider the equation of motion along the $y$ direction.

$$ M \ddot y = -Mg - k \dot y \implies \ddot y = -g - \frac kM \dot y $$

Solving for $\Delta y = y - y_0$, we have

$$ \Delta y = -g \frac Mk t - \dot y_0 - g \frac Mk + (\dot y_0 + g \frac Mk) e^{-\frac kM t} $$

For our case we will assume our flower petal starts at rest ($\dot y_0 = 0$), assuming it falls from some branch.

Let’s notice a few things about this solution.

For large $t$, the exponential can be neglected.

So $\Delta y$ follows linear motion for large $t$.

$$ \Delta y \approx -g \frac Mk t - g \frac Mk $$

Here the petal is moving at terminal velocity, where said terminal velocity is $g\frac Mk$ in the downwards direction.

The aforementioned movie states that flower petals move at $5cm/s$.

Setting the terminal velocity to $5cm/s$ and $g$ to $9.81 m/s^2$, we have

$\frac Mk = (5cm/s) / (981 cm/s^2) \approx 0.00510 s$

Assuming cherry blossoms weigh about a tenth of a gram,

we can approximate $k \approx 19.6 g/s = 0.0196 kg/s$.

Newton tells us that the general 2nd law is that the change of momentum is equal to the sum of acting forces.

With this we can interpret this rate of mass change as coming from this principle where some mass is being shifted to cause this force.

For our case this shifted mass is clearly the surrounding air.

Taking our petal to displace the amount of air it sweeps with its area, we can approximate this rate as $\rho_{air} A v$.

$\rho_{air} = 1.1839 kg/m^3$, taken from Wikipedia for density of air at 25 Celsius.

Setting this displaced air to $k$ so $k = \rho_{air} A v$.

Solving for $A = k/(\rho_{air} v) \approx 0.331 m^2$.

For a circular disk, this implies that $R \approx 0.325 m = 32.5 cm$.

This is a bit large for a flower petal!

I think this model is telling us that the flower petal must be relatively large to fall slowly at a rate of $5cm/s$.

So somehow we need to change our model to allow for smaller surfaces to fall slower.

In other words, we need to catch more air.

One idea to do this is to note that flower petals do not just fall straight down, but flutter about and can have quite complicated motions.

So to this end let’s extend our model to introduce fluttering.

Accounting for Petal Disk’s Geometry in Air Force

Let’s now use the geometry of the flower petal to develop a more sophisticated air force term.

Let’s derive a few key quantities beforehand.

With the CM coordinates as $(x, y)$, the position of a point on the flower petal some distance from its axis of rotation is $( x + h \cos(\theta) )\hat x + ( y + h \sin(\theta) )\hat y$.

We can derive a velocity of such points:

$$ \dot x \hat x + \dot y \hat y + h \dot\theta (- \sin(\theta) \hat x + \cos(\theta) \hat y ) = \dot r + h \dot\theta (- \sin(\theta) \hat x + \cos(\theta) \hat y ) $$

The latter two terms form a vector that is normal to the surface of the petal.

We will express the unit normal vector (area vector) as $\hat A = - \sin(\theta) \hat x + \cos(\theta) \hat y$.

So we can express the velocity vector as:

$$ v = \dot r + h \dot\theta \hat A $$

Now we can form our air force term.

The idea is that we want to account for the geometry of the petal.

The petal sweeps some volume, displacing the occupying gas’s mass.

To account for this, we want to only resist motion that sweeps out a volume.

This makes sense because for large, light, flat objects, dropping edgewise has almost no effect on the object.

On the other hand, dropping facewise will result in a much slower descent due to air resistance.

So for a small flat, rectangular object we suppose the following air force:

$$ dF_{air} = -k ( v\cdot d\vec A ) d\hat A $$

Integration will allow us to recover the full force.

Quick aside: for $|d\vec A|$ at a given $h$, we have $|d\vec A| =2 \sqrt{R^2 - h^2} dh$ as a thin strip of the petal, parallel to the axis of rotation.

Now let’s apply the differential new air force to our case:

$$ dF_{air} = -k (\dot r + h \dot\theta \hat A) \cdot (|d\vec A| \hat A) = -2k (\dot r\cdot \hat A + h \dot\theta )\sqrt{R^2 - h^2} dh $$

Now we can integrate to get $F_{air}$:

$$ \int dF_{air} = -2k\hat A \int_{-R}^{R} (\dot r\cdot \hat A + h \dot\theta )\sqrt{R^2 - h^2} dh = -k A (\dot r\cdot \hat A) \hat A $$

To calculate the torque we do a similar calculation:

$$ \tau_{air} = \int r_\tau \times dF_{air} = -2k \int_{-R}^{R} r_\tau \times \hat A (\dot r\cdot \hat A + h \dot\theta )\sqrt{R^2 - h^2} dh $$

where $r_h = h(\cos(\theta) \hat x+ \sin(\theta) \hat y)$.

This simplifies to:

$$ \tau_{air} = \int r_\tau \times dF_{air} = -\frac 14 k AR^2 \dot\theta\hat z $$

where we can evaluate the integral.

The $\hat z$ is the 3rd dimension, but it just represents the axis of rotation for the petal.

Now we can calculate the moment of inertia to complete the angular equation of motion2.

$$ I = \int |r_\tau|^2 dm = 2 \sigma \int_{-R}^R |h|^2 \sqrt{R^2 - h^2} dh = \frac 14 MR^2 $$

Putting it all together we have three equations of motion:

$$ \ddot\theta = -(k/\sigma) \dot\theta $$

$$ \ddot x = (k/\sigma) (\dot r\cdot \hat A) \sin(\theta) $$

$$ \ddot y = - g - (k/\sigma) (\dot r\cdot \hat A) \cos(\theta) $$

where recall that $\hat A = - \sin(\theta) \hat x + \cos(\theta) \hat y$ so

$\dot r\cdot \hat A = -\dot x \sin(\theta) + \dot y\cos(\theta)$.

This model has more complicated motion so it’s difficult to analyze.

One can notice that the $\theta$ equation of motion does not depend on the other variables and is readily solvable:

$$ \dot\theta = \dot \theta_0 e^{-k/\sigma t} \implies \Delta \theta = \frac { k\dot\theta_0 }\sigma e^{-k/\sigma t} $$

So if we start from rest, we can see that the petal does not rotate, but it is possible it could flutter.

Nonetheless, after some time the angle will stop changing, so with that reasoning let’s assume the angle is constant for analysis on $x$ and $y$.

Even with this assumption, the equations of $\dot x$ and $\dot y$ are obscure.

But in general it has this form:

$$\ddot r = -\mathbf b - \mathbf A \dot r$$

where:

$$ \mathbf b = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ g \end{bmatrix}, $$

$$ \mathbf A = \frac{k}{\sigma} \begin{bmatrix} \sin^2\theta & -\sin\theta \cos\theta \\ -\sin\theta \cos\theta & \cos^2\theta \end{bmatrix}. $$

We can solve for $r$ here:

$$ \Delta r = \left( \frac{1}{\kappa} \mathbf A \mathbf b - \mathbf b \right) \frac{ t^2 }2 + \left( -\frac{1}{\kappa^2}\mathbf A \mathbf b -\frac{1}{\kappa}\mathbf A \mathbf c_1 + \mathbf c_1 \right) t - \frac{1}{\kappa^2}e^{-\kappa t}\mathbf A \mathbf c_1 $$

where $\kappa = k/\sigma$.

There are a few differences from the constant case.

There is a terminal acceleration!

This acceleration only depends on $g$ and the orientation, $\theta$:

$$ a_t = -g \sin (\theta) (\cos (\theta) \hat x + \sin(\theta)\hat y) $$

This acceleration is similar, if not the same, as the acceleration of a block sliding down an inclined plane of angle $\theta$.

For a flat petal, there is no terminal acceleration.

Likewise, if the petal is aligned vertically there is maximal terminal acceleration.

Now, looking at the terminal velocity with $\dot r_0 = 0$, we have:

$$ \mathbf c_1 = \frac{1}{\kappa^2}\mathbf A \mathbf b $$

$$ v_t = -\frac{1}{\kappa^2}\mathbf A \mathbf b = g \cos (\theta) \left( \sin (\theta) \hat x - \cos(\theta) \hat y \right) = - \frac {g \sigma}{k} \cos (\theta) \hat A $$

Now we can see that the terminal velocity is aligned with the area vector.

There is also a dependence on the angle.

For a flat petal, there is maximal terminal velocity downwards.

On the other hand, for an upright petal, there is essentially no terminal velocity.

We could have a single flutter as the petal goes right or left as it falls, but it now has a generic terminal acceleration.

Thus, we need another modification of our model.

Deforming the Petal

For our modification, we do not want just a flat disk geometry for our petal.

To do that we can bend the surface of the petal geometry.

This is to allow for air to hit the surface non-uniformly.

Let’s recall the differential air force from the previous system:

$$ dF_{air} = -k ( v\cdot d\vec A’ ) d\hat A' $$

The $d\hat A$ can be modified to depend on $h$.

To implement this, let’s add a modification: $\theta \to \theta + \frac hR \alpha$.

Here $\alpha$ is a dimensionless parameter that measures the amount of bending.

As a result, our $d\vec A$ changes:

$$ d\vec A’ = |d\vec A| (- \sin(\theta + \tfrac{h}{R} \alpha) \hat x + \cos(\theta + \tfrac{h}{R} \alpha) \hat y) $$

Practically and realistically, this bending should be small.

So we can expand $d\vec A$ around $\theta$ for small $\alpha$:

$$ d\vec A’ \approx |d\vec A| \left(- \sin(\theta) \hat x + \cos(\theta) \hat y - \alpha \tfrac hR ( \cos(\theta) \hat x + \sin(\theta) \hat y)\right) + \mathcal O(\alpha^2) $$

Furthermore, we have:

$$ |d\vec A’| \approx |d\vec A| + \mathcal O(\alpha^2) $$

$$ d\hat A’ \approx - \sin(\theta) \hat x + \cos(\theta) \hat y - \alpha\tfrac hR ( \cos(\theta) \hat x + \sin(\theta) \hat y) + \mathcal O(\alpha^2) $$

We can simply write our differential area vector:

$$ d\vec A’ \approx |d\vec A| (\hat A - \alpha\tfrac hR \hat r_h) + \mathcal O(\alpha^2) $$

Note that $\hat A$ and $\hat r_h$ are perpendicular, $\hat A \cdot \hat r_h = 0$.

So our total force can now be evaluated:

$$ \int dF_{air} = A k (-(\dot r\cdot\hat A) \hat A + \alpha \dot\theta \tfrac{R}{4} \hat r_h ) $$

For torque we have:

$$ \tau_{air} = \int r_h\times dF_{air} = k \left(\tfrac \alpha R \dot r \cdot\hat r_h - \dot\theta\right) \frac{A R^2}{4} \hat z $$

Where we kept only up to first order in $\alpha$.

We leave the details of the integration to the reader.

Now, we can write the equations of motion:

$$ \ddot\theta = (k/\sigma) \left(\tfrac \alpha R \dot r \cdot\hat r_h - \dot\theta\right) $$

$$ \ddot x = (k/\sigma) \left((\dot r\cdot\hat A) \sin\theta + \tfrac 14 \alpha R\dot\theta \cos\theta \right) $$

$$ \ddot y = - g + (k/\sigma) \left(-(\dot r\cdot\hat A) \cos \theta + \tfrac 14 \alpha R\dot\theta \sin\theta \right) $$

Now, we have a more sophisticated model!

Nevertheless, this model has a semi-obvious problem: it’s hard3 to solve analytically.

In lieu of that, we can solve this differential equation numerically for several initial conditions for a static initial center of mass.

These numerical calculations can be found in the accompanying Pluto notebook.

Note that we also included the simplified air force of the form $-k’ \dot r$.4

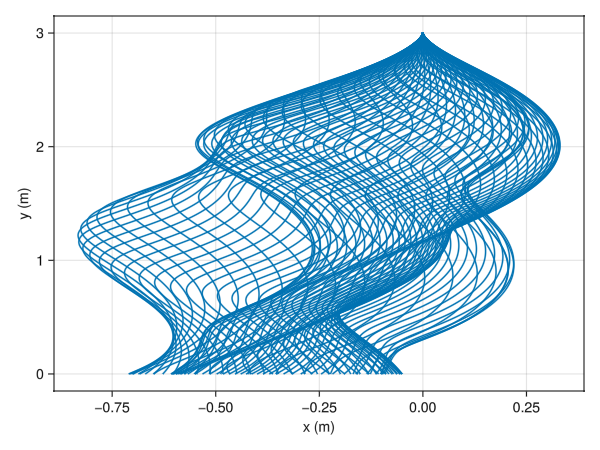

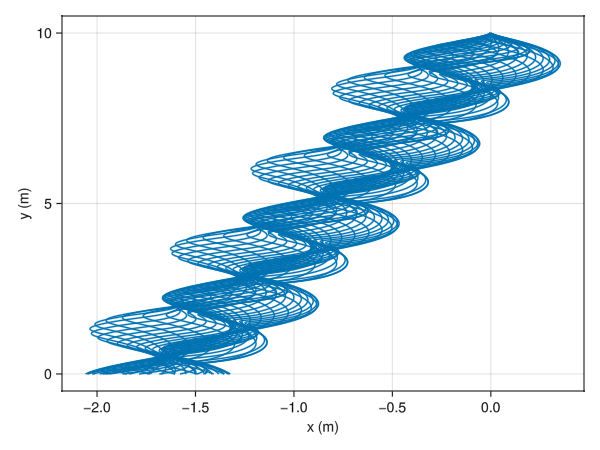

Sampling over a range of initial orientations we have the following petal falling paths:

Using “realistic” parameters, we were able to find petals that fall at $\sim72 cm/s$ — a far cry, but in the same ballpark, as $5 cm/s$.

One can check the notebook for the parameters used.

The parameters for the $72cm/s$ case are:

$k/\sigma = 20.0 s^{-1}$, $g = 9.81 m/s^2$, $R = 1 cm$, $\alpha = 0.03$, $y_0 = 10.0$, and $k’/M = 4.0 s^{-1}$.

I leave it to the reader to play with other constants in the notebook. Note there is leftward drift in the petal descent but I am not sure what the cause might be: numerical in nature or otherwise.

Conclusion

It’s possible with a more refined model and a clever choice of parameters to reproduce the 5 centimeters per second from the animated movie.

Nevertheless, it’s surprising to see how far one can get with the simple model presented in this post.

A possible next step would be to go fully numerical and simulate the petal in 3D, including flexing and bending, with air modeled as a fluid.

On the other hand, having a model that is as simple as possible and reproduces the behavior of sakura petals would also be a great direction to pursue.

Perhaps a simpler model can be derived that captures the essence while remaining more tractable than the final model of this article.

Further Reading:

- 5 Centimeters per Second

- A site to determine an quick apprixmation of a flower petal’s mass

- Pluto notebook used for the numerics

Appendix

Solving for Constant Air Force

We start with

$$ \ddot y = -g - \frac kM \dot y $$

We can rearrage the equation.

$$ \frac d{dt} \dot y + \frac kM \dot y = -g $$

We can solve for $\dot y$ using a first order ODE solving technique.

$$ e^{\frac kM t} \frac d{dt} \dot y + \frac kM e^{\frac kM t}\dot y = -ge^{\frac kM t} $$

$$ \frac d{dt} ( e^{\frac kM t} \dot y ) = -ge^{\frac kM t} $$

$$ e^{\frac kM t} \dot y = -g \frac Mk e^{\frac kM t} + C_1 $$

$$ \dot y = -g \frac Mk + C_1 e^{-\frac kM t} $$

$$ y = -g \frac Mk t + C_2 + C_1 e^{-\frac kM t} $$

Plugging in $t=0$, we can solve for $C_1$ and $C_2$.

$$ y_0 = C_2 + C_1 $$

$$ \dot y_0 = -g \frac Mk + C_1 $$

so

$$ C_1 = \dot y_0 + g \frac Mk $$

$$ C_2 = y_0 - \dot y_0 - g \frac Mk $$

$$ y = -g \frac Mk t + y_0 - \dot y_0 - g \frac Mk + (\dot y_0 + g \frac Mk) e^{-\frac kM t} $$

So the final solution is

Writing as the total displacement for the start, we have.

$$ \Delta y = -g \frac Mk t - \dot y_0 - g \frac Mk + (\dot y_0 + g \frac Mk) e^{-\frac kM t} $$

Solving for Accouting of Petal Disk’s Geometry Air Force

We can rearrage our equation

$$\ddot r + \mathbf A \dot r = -\mathbf b$$

where

$$ \mathbf b = \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ g \end{bmatrix}, $$

$$ \mathbf A = \kappa \begin{bmatrix} -\sin^2\theta & \sin\theta \cos\theta \\ \sin\theta \cos\theta & -\cos^2\theta \end{bmatrix}. $$

$$e^{\mathbf At}\ddot r + \mathbf A e^{\mathbf At} \dot r = -e^{\mathbf At}\mathbf b$$

Using the fact that $\mathbf A e^{\mathbf At} = e^{\mathbf At} \mathbf A$. We also defined a confined a convenience variable $\kappa := k/\sigma$

$$\frac{d}{dt}(e^{\mathbf At}\dot r) = -e^{\mathbf At}\mathbf b$$

At this point we can integrate, but since $\det \mathbf A = 0$, we need the explicit expression for $e^{\mathbf At}$. Notice that the property of $\mathbf A^2 = \kappa \mathbf A$5. This property will allow us to evaluate matrix exponential.

$$ e^{\mathbf At} = \sum_{n=0} \frac{1}{n!} (\mathbf A t)^n = 1 + \sum_{n=1} \frac{1}{n!} \kappa^{n-1} \mathbf A t^n = 1 + \mathbf A \frac 1\kappa \sum_{n=1} \frac{1}{n!} \left(\kappa t\right)^n $$

$$ e^{\mathbf At} = 1 + \frac 1\kappa ( e^{\kappa t} - 1) \mathbf A $$

Using this formula, we can plug in for $e^{\mathbf At}\mathbf b$.

$$ \frac{d}{dt}(e^{\mathbf At}\dot r) = -\mathbf b - \frac 1 \kappa ( e^{\kappa t} - 1) \mathbf A\mathbf b $$

Now we can integrate.

$$ e^{\mathbf At}\dot r = -\mathbf b t - \frac 1\kappa ( \frac {e^{\kappa t}}\kappa - t) \mathbf A\mathbf b + \mathbf c_1 $$

After multiplying by the exponential’s inverse, we can have the velocity.

$$ e^{-\mathbf At} = e^{\mathbf A(-t)} = 1 + \frac 1\kappa ( e^{-\kappa t} - 1) \mathbf A $$

$$ \dot r = e^{-\mathbf At} \left( -\mathbf b t - \frac 1\kappa \left( \frac {e^{\kappa t}}\kappa - t\right) \mathbf A\mathbf b + \mathbf c_1 \right) $$

$$ \dot r = (1 + \frac 1\kappa ( e^{-\kappa t} - 1) \mathbf A) \left( -\mathbf b t - \frac 1\kappa \left( \frac {e^{\kappa t}}\kappa - t\right) \mathbf A\mathbf b + \mathbf c_1 \right) $$

$$ \dot r = -\mathbf b t - \frac 1\kappa \left( \frac {e^{\kappa t}}\kappa - t\right) \mathbf A\mathbf b + \mathbf c_1 + \frac 1\kappa ( e^{-\kappa t} - 1) \left( -\mathbf A \mathbf b t - \left( \frac {e^{\kappa t}}\kappa - t\right) \mathbf A\mathbf b + \mathbf A \mathbf c_1\right) $$

$$ \dot r = \frac{1}{\kappa^2} (\kappa t-1) \mathbf A \mathbf b +\frac{1}{\kappa} \left(e^{-\kappa t}-1\right) \mathbf A \mathbf c_1 - \mathbf b t + \mathbf c_1 $$

We can orginized by factors of $t$.

$$ \dot r = \left( \frac{1}{\kappa} \mathbf A \mathbf b - \mathbf b \right) t -\frac{1}{\kappa^2}\mathbf A \mathbf b -\frac{1}{\kappa}\mathbf A \mathbf c_1 + \mathbf c_1 + \frac{1}{\kappa}e^{-\kappa t}\mathbf A \mathbf c_1 $$

Solving for $\mathbf c_1$ we find.

$$ \mathbf c_1 = \dot r_0 + \frac{1}{\kappa^2}\mathbf A \mathbf b $$

We can finally integrate one more time.

$$ \Delta r = \left( \frac{1}{\kappa} \mathbf A \mathbf b - \mathbf b \right) \frac{ t^2 }2 + \left( -\frac{1}{\kappa^2}\mathbf A \mathbf b -\frac{1}{\kappa}\mathbf A \mathbf c_1 + \mathbf c_1 \right) t - \frac{1}{\kappa^2}e^{-\kappa t}\mathbf A \mathbf c_1 $$