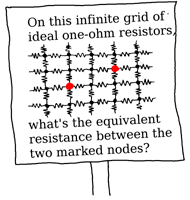

The Infinite Resistor Grid Nerd Snipe

I have to admit it. I got nerd sniped. Really, this blog post is about finding the equivalent resistance in question and more! To be transparent, after a good long think and retries I got the answer, so I will try to document/recollect that journey here. First, let’s set up the problem.

The Problem Set Up

We are given an infinite grid of resistors, each with a resistance of $R$.

The puzzle is that we want to find the equivalent resistance of this setup. The idea of an equivalent resistor here is: imagine we connect the two red dots with a battery. After we connect, there would be a current that goes from one red dot to the other—the direction depending on the polarity of the battery. Of course, there is a complicated flow of electricity as it disperses from one red dot to the other, but “averaging” over the resistors and their currents, one can replace all the resistors with one equivalent resistor that connects between the two red dots, leading to the same total current flow through the battery. So, the average current equation (Ohm’s Law) is

$$V = IR_\mathrm{equiv}$$

where

$$R_\mathrm{equiv} = \alpha R$$

and $\alpha$ is some numerical constant.

Solving the Problem

Starting out, let’s develop notation! Let’s label the nodes by two integers $(n, m)$. $n$, or the first number, is the horizontal direction that increases in the rightward direction. $m$, or the second number, is the vertical direction that increases upward1. We set, by convention, the origin to be on one of the red nodes. We label the numerical constant for the equivalent resistor for the case where the other red dot is at $(n, m)$ as $\alpha_{n,m}$. For us, we seek $\alpha_{2,1}$.

Here are some sanity checks to help guide us. For larger $|n| + |m|$2, $\alpha_{n,m}$ should be larger. This is because there are more resistors between the two red dots. The minimum of $\alpha_{n,m}$ should be at $n = m = 0$, since there is no resistance and we have a short. Also, our setup has some symmetry, so we expect that $\alpha_{n,m} = \alpha_{m,n} = \alpha_{-n,m}$. Let’s get into my first attempt at solving this problem!

My First Failed Attempt

Naively, I thought that by first finding solutions to the finite case, we could work our way up to the infinite case. To solve the finite case, we can use a combination of Ohm’s Law (Kirchhoff’s Law) and conservation of charge. For our case, this leads to an $N\times N$ matrix to invert where $N$ is the number of resistors. To find a non-zero current, we need to include an additional connection from the battery connecting two red dots. You can solve for $\alpha$ approximately by expanding the finite grid to be “approximately” infinite. Nevertheless, I was looking for the exact answer, so this first attempt would not do. Though another person has gone down this approximation route.

My Second Successful Attempt

Like a lot of problems in physics, usually a Lagrangian helps. In this case, we can construct a Lagrangian where the dynamic variable is the electric potential. Instead of a battery, we include a source current of $J$ at the origin and a sink current, $-J$, at $(n, m)$. Let’s write down the Lagrangian.

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} L = \int dt \sum_{n, m = -\infty}^{\infty} &\frac 12 \left(\dot\phi_{n,m}\right)^2 - \frac 1{2R} \left(\phi_{n+1,m} - \phi_{n,m}\right)^2 - \frac 1{2R} \left(\phi_{n,m+1} - \phi_{n,m}\right)^2\\ &+ J \phi_{0, 0} - J \phi_{n’, m’} \end{aligned} \end{equation}

With this Lagrangian, we can vary with respect to $\phi_{k, l}$, setting the time dependence to zero.

\begin{equation} \frac 1R \left( 4\phi_{k,l} - \phi_{k+1,l} - \phi_{k-1,l} - \phi_{k,l+1} - \phi_{k,l-1} \right) = J \delta_{k,0}\delta_{l,0} - J \delta_{k,n’}\delta_{l,m’} \end{equation}

For us, we just need to solve for $\phi_{m,n} - \phi_{0,0}$, giving us the potential difference to find the effective resistance3. To help us toward this end, we can use the Discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT). Starting with a 1D discrete function $f$ over $n$, $f(n)$, we can define its Fourier transformed version, $\tilde f(\omega)$, as

\begin{equation} \mathcal L\{f\}(\omega) \equiv \tilde f(\omega) := \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty f(n) e^{ - i n \omega } \end{equation}

The inverse transformation is an integral over the complex argument.

\begin{equation} \mathcal L^{-1}\{ \tilde f \}(n) := \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_0^{2\pi} \tilde f(\omega) e^{in\omega} d\omega \end{equation}

Easily, we can extend to 2D discrete functions $g(n, m)$ where

\begin{equation} \tilde g(\omega, \nu) := \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty \sum_{m=-\infty}^\infty g(n, m) e^{ i ( n \omega + m \nu ) } \end{equation}

with the corresponding inverse transformation:

\begin{equation} g(n, m) := \frac{1}{( 2\pi )^2} \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} \tilde g(\omega, \nu) e^{i (n\omega + m\nu)} d\omega d\nu \end{equation}

Noting that

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \mathcal L \{f(n - k)\} &= \tilde f(\omega) e^{-i\omega k}\\ \mathcal L \{\delta_{n, k}\} &= e^{-i\omega k}\\ \mathcal L \{\phi_{n, m}\} &:= \tilde \phi(\omega, \nu) \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation}

for generic functions over $n$ and constant integers $k$. We can write our pre-simplified DTFT-transformed equation of $\phi_{k, l}$ as

\begin{equation} \frac 1R \left( 4 - e^{i\omega} - e^{-i\omega} - e^{i\nu} - e^{-i\nu} \right) \tilde \phi(\omega, \nu) = J - J e^{-i(\omega n’ + \nu m’)} \end{equation}

Using a trigonometric identity and algebra, we can solve and simplify for $\tilde \phi$:

\begin{equation} \tilde \phi(\omega, \nu) = RJ \frac{1 - e^{-i(\omega n’ + \nu m’)}}{2\left(2 - \cos\omega - \cos\nu \right)} \end{equation}

Inverting the DTFT, we can find $\phi_{n, m}$. 4

\begin{equation} \phi_{ n, m } = \frac{RJ}{( 2\pi )^2} \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{1 - e^{-i(\omega n’ + \nu m’)}}{2\left(2 - \cos\omega - \cos\nu \right)} e^{i (n\omega + m\nu)} d\omega d\nu \end{equation}

Now let’s compute the potential difference with respect to the origin, $\phi_{n, m} - \phi_{0, 0}$, setting $n’ = n$ and $m’ = m$:

\begin{equation} \phi_{ n, m } = \frac{RJ}{( 2\pi )^2} \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{e^{i (n\omega + m\nu)} - 1 -1 + e^{-i(\omega n + \nu m)}}{2\left(2 - \cos\omega - \cos\nu \right)} d\omega d\nu \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \phi_{n,m} - \phi_{0,0} = \frac{RJ}{( 2\pi )^2} \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{\cos(n\omega + m\nu) - 1}{\left(2 - \cos\omega - \cos\nu \right)} d\omega d\nu \end{equation}

So, the effective resistance between two arbitrary points $( n, m )$ apart is

\begin{equation} R_{n,m~\mathrm{equiv}}/R \equiv \alpha_{n,m} = \frac{1}{( 2\pi )^2} \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} \frac{1 - \cos(n\omega + m\nu)}{\left(2 - \cos\omega - \cos\nu \right)} d\omega d\nu \end{equation}

This integral is tough but numerically calculable.

For $n = 2$ and $m = 1$, we have $\alpha_{2,1} \approx 0.773240$. Apparently, this $\alpha_{2,1}$ is exactly $4/\pi - 1/2$.

Here are some more values of $\alpha_{n,m}$:

| n \ m | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0000 | 0.5000 | 0.7268 | 0.8606 | 0.9540 |

| 1 | 0.5000 | 0.6366 | 0.7732 | 0.8808 | 0.9648 |

| 2 | 0.7268 | 0.7732 | 0.8488 | 0.9244 | 0.9919 |

| 3 | 0.8606 | 0.8808 | 0.9244 | 0.9762 | 1.0279 |

| 4 | 0.9540 | 0.9648 | 0.9919 | 1.0279 | 1.0671 |

Further Reading

- the “approximation solution article”

- some related literature: article 1 and article 2

- pluto notebook to play around with the integral

Sorry to any computer scientists. ↩︎

This is the taxicab distance. ↩︎

Note that we already know the total current through the “battery”. ↩︎

Notice the change of variable label. ↩︎